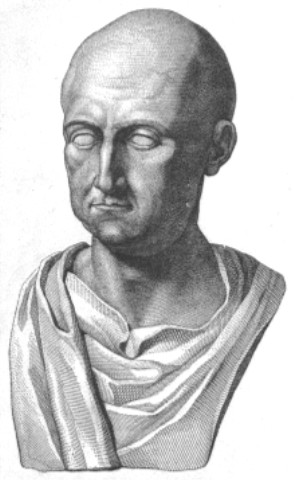

Publius Scipio African : born about 235/236 BC in Rome, died in 183 B.C. in LiternumTitle: Consul of the Roman RepublicA Roman consul who acquired great celebity by defeating the Carthaginian generals, Asdrubal and Mago, in Spain, and Annibal in Africa: he terminated the second Carthaginian war, and for his service: obtained the surname of Africanus. He died in the year 571 of Rome, and 183 years before Christ. Scipio was remarkable for his filial affection. In the second Carthaginian war, when he was about seventeen years of age, and his father, as one of the Roman consuls, was engaged in opposing the progress of Annibal into the Roman territory, a battle took place, in which the Roman troops gave way, and the consul, dangerously wounded, was surrounded by the enemy. The young Scipio, who was attended by a troop of select horseman as a guard, exhorted them to rescue his parent from destruction. They hesitated, and he furiously spurred his own horse in the midst ot the combatants: his attendants, instigated by his example, followed: the body of the enemy was separated by the shock, and the life of his father was saved.

In the year of the city 539, when still young, he offered himself a candidate for the office of curule edile. The plebeian tribunes opposed his pretentions, on account of his youth. He, however, replied, that if it were the will of the citizens to make him edile, he was old enough to fulfil the duties of the Office and such was his popularity, that he was elected, by a great majority of votes. About two years after this, the Roman army was defeated in Spain; his uncle and father were both killed, and many of the Spanish provinces abandoned their alliance with the Romans. A successor to these two eminent men could not easily be found; and, in a public assembly, held for the purpose of considering the disastrous state of the Roman affairs in that country, no candidate appeared for so dangerous an office. The people looked, in vain, to the senators to make the appointment, and the senate, in their difficulty, were desirous of leaving the appointment to the people. But each party was unsuccessful. No one could be prevailed with to accept the command. A general silence ensued, and a general despondency. At length Scipio arose, and declared himself ready to pursue the footsteps of his father and uncle, though these should lead him to labours, to dangers, and even to death. The eyes of the whole assembly were instantly turned upon him, and the universal acclamations of favour and applause, testified the hopes which persons of all ranks were inclined to entertain of his success. According to Polybius, he was at this time twenty-seven years of age; but, according to Livy and Appian, he was only twenty four. Notwithstanding his youth, it appeared, on taking the votes, that he was unanimously elected. No sooner, however, was the election terminated, than the people began to reflect on the precipitate manner in which they had acted; and to discover that they had been influenced rather by their inclination than their judgment. His early age was the principal cause of their uneasiness; but some of them began to forbode evil, in consequence of the recent misfortunes of his family. It was, however, too late to deliberate, after the appointment had been made. In this early part of the history of Scipio, it may not be improper to speak of his piety: and to notice that, even from the period at which he assumed the manly gown, he seldom transacted any business, either public or private, without first paying his devotions to heaven. This practice, says Livy, which he observed through his whole life, induced many persons to believe that his origin was divine. The same historian informs us, that when he was peculiarly desirous of effecting any purpose with the multitude, he would state that it had been recommended to him in a vision, or that it was the consequence of some admonition impressed upon his mind by the gods. But on this subject we labour under two difficulties: one, as to the actual state of the fact, whether he meant to impose a fiction upon the people, or whether he might really feel his mind so influenced, as to believe that he was favoured with divine inspiration. The other difficulty lies in the imperfect religious notions of the ancients, and the consequent incorrectness of explanation, in the historians, of what might really be the religious feelings of those persous respecting whom they wrote. In the year of the city 541, Scipio sailed from Rome, with a fleet of thirty ships; and, coasting allong the shore of the Tuscan sea, the Alps, and the Gallic Gulf, he disembarked at Emporium, a town founded by the Greeks. He thence ordered his fleet to follow, whilst he marched by land to a city called Tarra. At this place he held a convention of the Roman allies; and ambassadors were sent to him from several of the Spanish provinces. He afterwards visited the winter quarters of the Roman army, and was rejoiced to find that the enemy had not been permitted to derive much advantage from his recent success. The troops of the enemy were, at this time, in winter quarters, in different parts of the country. One division, under Asdrubal the son of Gisco, was at Gades, near the sea; another, under Mago, was in the interior of the country; and a third, under Asdrubal the son of Amilcar, was in the vicinity of Saguntum. Instead of pursuing what appeared to other persons the most obvious measures, Scipio formed a plan of action, which was alike impenetrable to his own army and unsuspected by the enemy. As soon was the opening of the spring permitted him to move, and he had concentrated and arranged his forces, he resolved not to attack the army of the enemy, but to make an unexpected attack on the city of New Carthage, This was not only a wealthy place, but was filled with a vast quantity of arms, ammunition, and stores. It was also conveniently situated, as a place of embarkation for Africa; and had an harbour sufficiently capacious to admit, if requisite, the whole Roman fleet. If he could succeed in taking this city, he knew that he should immediately deprive the enemy of some of his most important means of carrying on the war. A sudden attack was consequently made, both from the land and the sea; with some difficulty the Roman troops succeeded in scaling the walls; and, a short time afterwards, they rendered themselves masters of the place. The quantity of military stores and engines of war which it contained, was very great. Gold and silver to an immense value, was brought to the general. Among other articles, there were two hundred and seventy six silver bowls, each nearly a pound in weight; eighteen thousand three hundred pounds weight of wrought and coined silver; and a prodigious number of silver vessels and utensils. There was also an astonishing supply of wheat and barley; and as much brass, iron, canvass, hemp, and other similar materials were found, as would have equipped a fleet of one hundred and thirteen ships. In most respects Scipio afforded a brilliant example of united heroism and humanity; but, in the present as well as in a few other instances, he suffered himself, by a practice common among the Romans, to be led into the commission of great cruelty. To deter the garrisons of fortified places from continuing the defence of them until they should be attacked by storm, and should thus occasion an unnecessary loss of lives to the besiegers, it was customary, when a place was so taken, not only to plunder it, but to commit indiscriminate slaughter : among the garrison, and even among those of the inhabitants who had no concern in its defence. In the present instance, as soon as a certain number of troops had entered, Scipio gave direction to a portion of them to destroy all whom they should meet; and, at a particular signal, the slaughter ceased and the pillage of the place commenced. After this, the prisoners were collected, and to the number of ten thousand, were brought before Scipio, in two separate bodies. The first of these consisted chiefly of the free citizens, with their wives and children; and, in the other, were the artificers and tradesmen of the city. Having exhorted the former to enter into the friendship of the Romans, he dismissed them. To the artificers, about two thousand in number, he said that, for the present, they were the slaves of the Roman commonwealth; but that, if they served their masters with alacrity in their several trades, they might obtain their freedom, as soon the war with the Carthaginians should be terminated. From the other prisoners he selected many to serve on boards his ships, on an asaurance similar to that which he had made to the artificers. And he treated them all with so much greater kindness and humanity than had been expected, that he gained the general confidence of the citizens, and secured their attachment both to himself and his cause. The Carthaginians had kept, in this city, numerous hostages which they had received from the different states of Spain. The whole of these, several hundreds in number, Scipio, with great policy, sent back to their relations, and without requiring for them any ransom. Among other prisoners that were brought to him, was a young Spanish female, of high rank and exquisite beauty. This lady had been betrotbed to a Celtiberian prince named Allucius, by whom she was passionately beloved. Scipio sent for her parents and her betrothed husband; and, on their arrival before him, he addressed himself to the latter, stating that he was desirous of giving the young lady, in safety, to that person only, who, from the accounts he had received, appeared to be truly worthy of her. The youth, overwhelmed with joy, invoked the gods to recompence such exalted goods ness. The parents of the lady had brought with them a valuable present of gold, intending to offer it in purchasing her liberty; and, when she was restored to them without ransom, they entreated of Scipio to accept that as a present, which he might have claimed as a right; assuring him that they should esteem themselves as much satisfied, by his compliance with their wishes in this respect, as they had been by his restoration of their child. Unwilling to reject a solicitation so urgent, he ordered the gold to be brought; then calling Allucius to him, he said: Besides the dowry which you are to receive from your father-in-law, you must accept this marriage present from me. The gratitude of the young man for these unexpected honours and presents, induced him to make a levy among his dependants; and, in a few days, he returned to Scipio with a troop of fourteen hundred horsemen, to serve in the Roman army. Towards the inhabitants of the country Scipio adopted the most conciliatory conduct. He returned all those who had been made prisoners. The wife and children of a distinguished commander, one of his opponents, had been taken: these also were sent back. It was impossible for Scipio to have adopted any mode of procedure better calculated to effect his designs of rescuing Spain from the power of the Carthaginians, and bringing the whole of that country into an alliance with Home, than by humanity, rather than by the force of arms. He next attacked and defeated the army of Asdrubal, taking upwards of twelve thousand prisoners; of whom he sent home, without ransom, all that were Spaniards. So highly were this people delighted with his moderation, that a deputation, of their chiefs waited upon him, for the purpose of soliciting him to assume the sovereignty of their country, and addressed him by the title of king. He, however, replied to them, that he could not abandon the cause of his country; and; consequently, that he neither would be a king nor would suffer himself to be called so; and that, in future, they must address him only by the title of general. The Carthaginians, not long after this, were compelled to relinquish the whole of their possessions in Spain; and Scipio, now contemplating the probability of his being employed to combat this people in their own country, resolved, as preparatory to his future operations, to conciliate, as far as possible, the friendship of the several states adjacent to the Carthaginian territory. With this view he sailed, in two galleys, from New Carthage to the opposite coast of Africa, in a hope of being able to detach Syphax, king of the Massaesylians, from his alliance with the Carthaginians. It happened that, at this very time, Asdrubal, driven out of Spain, entered the same harbour as Scipio. He had seven galleys, and might easily have overtaken and seized the Roman general, before he reached the shore; but, amidst the tumult which took place, in preparing, on one side for attack, and on the other for defence, both parties entered the harbour, and when there, neither of them dared to excite a disturbance, lest he should give offence to Syphax. After they hadlanded, Asdrubal proceeded to the king, and was followed by Scipio. To Syphax it was a very flattering and a very singular occurrence, that the generals of two great nations should, on the same day, have come to solicit his friendship and alliance. He invited them both to his palace, hoping that, by an amicable conference, some arrangements might be made, which should end in a general pacification. Scipio declared that he had no personal enmity against the Carthaginians, but said that he was not furnished with authority to enter into any negociation for peace, without orders from the Roman senate. Syphax, however, prevailed with the two generals to sup together at his table, and was extremely delight with the affability and conversational talents of Scipio: even Asdrubal strongly expressed his admiration of them. The influence of Scipio, and a dread of the Roman power, induced Syphax to enter into a private treaty with the Romans, by which he agreed to abandon his alliance with Carthage. On his return to Spain, from which country he had been absent only four days, Scipio retook some cities, the inhabitants of which had revolted from the Romans; and, as a terror to others, be permitted his soldiers to commit great devastation in them. The inhabitants of one of them are said to have been all destroyed. The operations of Scipio in Spain ceased in the thirteenth year after the commencement of the war, and in the fifth year after he had succeeded to the command of the army. On his return to Rome he was unanimously chosen consul; and, of the plunder he had obtained, he deposited, in the public treasury, fourteen thousand three hundred and forty-two pounds weight of silver in bars, and a prodigious quantity of specie. The Romans now became extremely anxious that he should transfer the seat of war into Africa. Many of the generals, however, jealous of his glory, strongly opposed this project; and even Fabius Maximus, though bending beneath the weight of years and military honours, expressed much uneasiness at Scipio's rising merit. In a speech, which he made before the Roman senate, he endeavoured to show that an expedition into Africa, would be attended with great danger, particularly if it were entrusted to the care of so young at man. In consequence of this opposition, Scipio had not so unlimited a power given to hit as he had expected. He, however, obtained the command of the Roman fleet which was kept on the coast of Sicily; and had permission, if he thought proper, to make a descent on the coast of Africa. When he arrived in Sicily, he formed a corps of three hundred men, in the flower of their age and the vigour of their strength. These he did not simply with arms, and kept ignorant of the purpose for which they were reserved. He then chose three hundred Sicilian youths of distinguished birth and fortune, whom he appointed, as horsemen, to pass over with him into Africa. This service appeared to them very severe. To be removed so far from their friends, and to be exposed to fatigue and danger, excessively distressed them. Scipio stated that, of them were afraid of the service, they had only to declare their fears or disinclination, and they should be excused. One of them did so, and Scipio told him that he approved his candour and would provide him a substitute. It was, however, requisite that, to this person, he should deliver his horse, arms, and other implements of war, and that he should muse him to be trained for the service. With these terms be readily complied, and Scipio placed under his care one of the three hundred young men whom he had in readiness. All the other youths, seeing their comrade thus excused, adopted the same plan. By this strastagem the Roman general, without any expence to the public, was enabled to provide a corps of three hundred excellent horsemen, who afterwards performed for him many important services. Scipio afterwards selected, from among his soldiers, all chose on whom he could fully rely; and thus he had a select and powerful force. He embarked from Sicily, in four hundred transports, and tidy ships of war, all of which safely reached the African coast. On his landing, the people of the whole adjacent country were so excessively alarmed, that they fled in every direction, driving before them all their cattle, and desolating the whole surrounding district. Scipio was shortly afterwards joined by Masinissa, king of Numidia, with a small force of cavalry; but he found that Syphax had abandoned tho Roman interest, and renewed his engagements with the Carthaginians; and had even strengthened his alliance with that people, by marrying Sophonisba, the daughter of Asdrubal. Besides several other advantages, the Romans gained a complete victory over Asdrubal, which enabled Scipio to proceed into the country, and to lay siege to Utica. But, being unable to take this city before the approach of winter, he retired into winter quarters in its vicinity. Syphax had now joined the Carthaginians; and their united armies approached the Roman entrenchments, near Utica. Scipio defeated them, with so great a loss, that the inhabitants of Carthage, in the utmost consternation, began to strengthen the walls and outworks of their city. Every one exerted himself, to the utmost, in bringing, from the country, such things as were requisite for sustaining a siege. The Carthaginians had now no army left, capable of checking the progress of Scipio, except that of Annibal. They, consequently, recalled him, and the whole of his forces, from Italy; but, before his arrival, Syphax was wounded and made prisoner by Masinissa and the Roman general Laelius; and Asdrubal, who had been oppressed by the hatred of his fellow-citizens, from a suspicion that he had held a correspondence with the Romans, had destroyed himself by poison. The conference took place within the view of both armies. It is said that the two generals were astonished at the sight of each other; and that, when they approached, they stood for some moments in profound silence. Annibal was the first who spoke. Happy would thave been (said he,) if the Romans had never coveted any thing beyond the extent of Italy; nor the Carthaginians beyond that of Africa; but that each had remained contented with the possession of those fair empires which nature itself seems indeed to have circumscribed. Such was the observation of that general who, after the battle of Carma, was master of nearly all Italy, who, afterwards, advanced to the vicinity of Rome, fixed his camp within five miles of the city, and there deliberated in what manner he should dispose of the Romans and their country. Behold me now (he continued) recalled to Africa, and holding a conference with a Roman general, to treat for the deliverance of my own country. Annibal, however, was either too fearful of making concesssions or Scipio too confident in his means of prosecuting the war with success, for the contest to be yet amicably terminated. Each commander retired to his army, stating his resolution to abide only by the decision of a battle, and immediate preparatiom were made for action. On the ensuing day, a conflict, one of the most tremendous that has been recorded in the annals of the world, took place, and hastened the termination of what is called the second Punic or Carthaginian was Annibal was totally defeated, and with a loss of more than forty thousand men, one hundred and thirty-three military standards, and eleven elephants. During the confusion of the retreat, he escaped, with a few horsemen, to Hadrumetum, after having, in vain, used every effort to rally his troops. He thence returned to Carthage, in the thirty-sixth year after he had left it, a boy. On the senate being assembled, he asserted to them that the Carthaginian forces where wholly vanquished, and that an immediate peace could alone save his country from ruin. In the mean time, Scipio pillaged the enemy's camp, and conveyed an immense booty to the sea-coast, to be embarked thence for Italy. The Carthaginians sent ambassadors to Scipio, to sue for peace. This was granted, on condition that they should surrender to the Romans all the deserters and prisoners which they had taken, all their ships of war, except ten, and all their trained elephants: that they should immediately give possession, to the Romans, of all the places they held in Italy and Sicily, and all the islands betwixt Africa and Italy; and that they should not make war either in or out of Africa, without permission of the Roman government; and that, for fifty years, they should pay an annual tribute to Rome. These terms, severe as they may seem to us, were considered moderate by the ancients. Velleius Paterculus, denominates "Carthage a monument of the clemency of Scipio;" and Livy says that "the Romans afforded a signal proof of their moderation, in the peace which was granted to Annibal and the Carthaginians As soon as all the arrangements for peace were complete, Scipio embarked his army, and returned to Italy; and so delighted were the Romans with his success, that not only the inhabitants of the towns, through, which he passed, flocked together to see the deliverer of their country, but crowds of people, even from distant parts of the country, almost filled up the roads. He entered Rome in triumph, at the head of a splendid cavalcade; and carried into the treasury one hundred and twenty-three thousand pounds weight of silver. It was after this triumph, and in consequence of his successes against the Carthaginians in Africa, that Scipio was honoured with it surname of Aricanus. In the year of the city 553 of Rome, he and Publius AElius Paetus were elected censors. Not long after this we find him, in the Roman senate, with true generosity and nobleness of mind, defending the cause of Annibal. Since the late peace, Annibal had assiduously employed himself, at Carthage, as a civil magistrate with leading member in the legislative assemblies of his country. In these assemblies he resolutely and successfully defended the lives and property of his countrymen against the power, the insolence, and the tyranny of the Carthaginian judges. He also effected many important reformations in the revenue of his country; and, as it was then a period of great distress, he insisted that, if all the arrears which were due to the public were paid, the exigencies of the state would be supplied. Conduct like this occasioned a great out cry against him, by persons who had long been preying upon the public property. These found means to instigate even the Romans against him; and to induce the senate to send ambassadors to Carthage on the subject. Scipio, however, long and earnestly contended that it was beneath the dignity of the Roman senate, to the accusers of such a man as Annibal; and that they ought to be satisfied with having humbled him in the field, and not now to be influenced against him by the calumny and detractions of self-interested persons. Six years after this, Scipio was a second time elected consul, and had, for his colleague, Tiberius Sempronius Longus. His hope, in this year standing for the consulate, is supposed to have been that he might either be sent into Asia, to commence a new war against Antiochus, king of Syria, who had menaced Europe with an invasion, or that he might obtain the province of Spain, to settle the tranquillity of that country, which he had formerly conquered, and where Cato had recently acquired great glory. He obtained the latter, but, when he arrived there, he found that the success of Cato had left him nothing of importance to finish. After the termination of his consulship, war was declared against Antiochus, and Scipio accepted the office of lieutenant-general under his brother, in an expedition which was fitted out against that monarch, The two Scipio's landed, with their army, in Greece; and, having passed through Thessaly, Macedon, and Thrace, they crossed the Hellespont, into Asia. Annibal, who had been driven from Carthage, and had sought protection in the states of Asia, had told Antiochus that, if he did not find employment for the Romans at home, he would soon be under the necessity of fighting in Asia; for those republiscans (said he) aim at nothing less than the empire of the world. It was now that Antiochus, for the first time, ascertained the correctness of this counsel. Alarmed for the safety of his dominions, he sent an ambassador to the Romans to sue for peace. The ambassadors, unable to arrange any satisfactory terms with the council appointed to receive them, obtained a private interview with scipio, and offered to him, from Antiochus, the restoration of his son, who was then a prisoner in the Syrian' camp, together with a present of an immense value, and even a share in the government, if, through his influence, peace could be obtained. The patriotic Roman thus replied: I should esteem my son the greatest gift that could be bestowed by royal munificence; any favour beyond this, my honour would not suffer me to accept. If the king restore my son, I shall ever acknowledge the obligation, and, in return, shall rejoice in the opportunity of testifying any similar mark of respect for him. Further I cannot go. My public character is sacred, and shall be unimpeached: in my official capacity I will neither receive not confer any private favour. The proposals of Antiochus were rejected, yet he had the generosity to restore the son of Scipio, and without ransom. The Roman army passed through Troy; and, after it had crossed the river Hyllus, offered battle to Antiochus, near the city of Magnesia. Scipio had been seized with an illness which prevented him from being present at the conflict that took place. In the Syrian army were marshalled a vast number of camels, and fifty-four large elephants, each carrying a tower filled with slingers and archers: there was also a long range of war-chariots, armed with scythes from the centre of the wheels. The number of soldiers was, in the whole, about eighty-two thousand, and that of the Roman troops not more than twenty-eight thousand; yet the Romans were by no means intimidated, and, before Scipio could join him, the consul had obtained so complete a victory, that Antiochus was glad to submit to such conditions of peace, as the Romans chose to grant. After this we find Scipio again in Rome, where, for his eminent services, he obtained the appellation of the great. For some time after his return from Africa, the Romans had heaped upon him all possible honours. The people had wished to make him even perpetual consul and dictator; but, more desirous of meriting than of obtaining honours, he severely reproved them for proposing to place him in a station which was incompatible with the liberty of his country. After a little while, however, he experienced, what he had often before observed towards others, the mutability of popular applause. At the instigation of Cato, a prosecution was instituted against him, on a charge of having received, from Antiochus, a sum of money, to obtain for him advantageous terms of peace. The conqueror of Asdrubal, of Annibal, and of Carthage; the man whom, not long before, they had been so anxious to appoint perpetual consul and dictator, was now reduced to make his defence as a criminal; and this he did with the same magnanimity which had distinguished all his actions. As his accusers, from want of proofs, used only invective, he contented himself, on the first day, with the usual defence of great men on similar occasions, a recital of his services and exploits; which was received with great applause. On the ensuing day, he said: Tribunes of the people, and you, my fellow-citizens, it was on this day that I conquered Annihal and the Carthaginians: let us hasten to the capitol, and offer our thanksgivings to the gods, and pray that they may always grant to you generals as successful as l have been. The people followed him, and the tribunes and crier of the court, were left nearly alone. The accusation was renewed a third time, but Scipio now either refused, or was unable to appear: his brother alleged that he was so ill as to be unable to attend: and Livy asserts that the trial terminated by the severest reproaches being thrown upon his accusers. Scipio had long and well known what value to set on popular favour. The multitude (said he, on one occasion) is easily deceived. It is impelled by the slightest force to every side; it is susceptible of the same agitation as the sea. For, as the see, though in itself calm and stable, and without the appearance of danger, is no sooner set in motion by some violent blast, than it resembles the winds themselves which raise and ruffle it; so, in precisely the same manner, does the multitude assume an aspect conformable to the designs and the temper of those leaders, by whose counsels it is swayed and agitated. Disgusted with the ingratitude of his countrymen, and having now learned to despise both popular applaused and popular condemnation, he retired, as a voluntary exile, to his country house at Liternum, on the sea-shore, near Cuma, where, during the remainder of his life, he chiefly employed himself in agriculture and study, and in conversation with the best-informed and most honourable men of his time. Two hundred years after the death of Scipio, the philosopher Seneca visited his house and tomb, and thus speaks of him: Under the roof of Scipio, I now write. I have performed my homage at his tomb; and confidently do I believe that his soul is now above, whence it descended to bless our world. His moderation and his piety each demand our admiration, and more, perhaps, when he left his country, than when he saved it. Authorities-Livy, and Plutarch. |