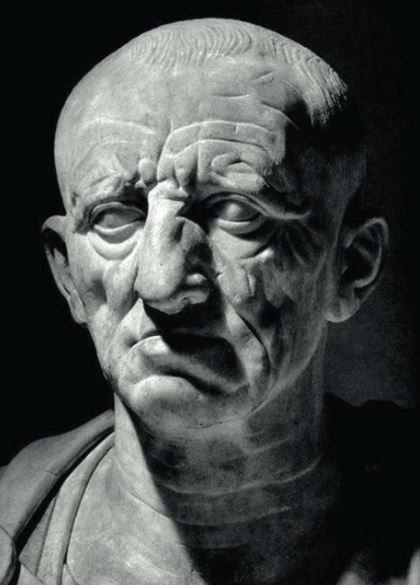

Marcus Porcius Cato or Cato the Elder : born 234 B.C. in Tusculum, died in 149 B.C. in RomaTitle: Consul of the Roman RepublicAn illustrious Roman, remarkable for bravery, temperance, and justice; and for the severity of his manners; and, in the latter part of his life, for avarice, and for an inveterate enmity against Carthage. He died at the age of about ninety years, in the year of Rome 605, and 149 years before the birth of Christ. The singular austerity of his own manners, and the important reformation which he effected in those of his countrymen, have obtained for this eminent Roman, a high degree of celebrity.

He was born about two hundred and thirty years before the Christian era, at Tusculum, a town twelve miles east from Rome. The name of his family was Priscus, but he received the appellation of Cato, on account of his great prudence. His father was of plebeian rank, but a military officer, who had served, during several campaigns, in the Roman army. Cato is said to have had a harsh countenance, red hair, and grey eyes; and an inflexibility of character which, in some degree, corresponded with the harshness of his features. We are told that, even from his infancy, he indicated, by his mode of speaking, by his countenance, and even by, his childish recreations, an extraordinary firmness of mind. He always persevered in accomplishing what he undertook, however unsuited it might have been either to his inclination or his strength. He was rough towards those who flattered him, and wholly untractable when threatened. He was rarely seen to laugh, or even to smile; and was not easily provoked to anger; but, if once incensed, it was not without great difficulty that he could be pacified. From a very early period of his life, Cato accustomed himself to endure hardships and fatigue. He also studied the graces of eloquence; and, even whilst a boy, was considered an excellent orator. The first tendency of his ambition was to military glory. He became a soldier at seventeen, and served in the Roman army against Annibal, when that commander was in the height of his prosperity. As a soldier his courage was invincible. He always marched on foot, bearing his own weapons, and attended only by one servant, who carried his provisions; and so ahstemious was he, that he was contented with whatever was set before him. When he was not immediately engaged in military duty, he himself often turned cook, and assisted in dressing, his own dinner. But his conduct in retirement was much more interesting than his character as a soldier. In the country of the Sabines he had a little cottage and farm, which had been left to him by his father, and had formerly belonged to Manlius Curius Dentatus, whose memory he greatly revered. At this farm, during the early part of his life, Cato chiefly resided. He was delighted in reflecting on the smallness and meanness of the dwelling; and, on the character and virtues of the man, who had retired to it after three triumphs, and who had cultivated, with his own hands, the grounds attached to it. At this cottage it was that the ambassadors of the Samnites had found Curius Dentatus, in his chimney corner, employed in dressing turnips; it was here that they offered to him a large present of gold, which he, unhesitatingly, rejected, observing, that a man who could be satisfied with a supper of turnips, had no need of gold. Influenced by this example, Cato adopted every means of increasing his own labour, and retrenching his establishment and expenses. Valerius Flaccus, a nobleman of great eminence, possessed an estate contiguous to the farm of Cato; and he had often heard his servants speak of the laborious and temperate life of his neighbour. Among other things, they told him that Cato was accustomed to go, early in the morning, to the little towns in the neighbourhood; for the purpose of pleading the causes of such persons as applied to him; that, thence he would return to his farm, where, in a coarse frock, if it were winter, or naked if it were summer, he would labour with his domestics, and afterwards sit down and partake of their homely food. They related many other instances of his moderation and condescension; and recited many of his sayings, which exhibited great goodsense, and a correct knowledge of mankind. In short, the accounts which reached Valerius, concerning his neighbour, were altogether so surprising, that he was resolved to call upon him. He did so, and, astonished at the singularity of his character and his extraordinary talents, he became interested in his welfare. He made him known to several other noblemen; and, soon afterwards, prevailed with him to leave his retirement, and become a candidate for public honours. Thus, from a little village and a country life, was Cato launched into the Roman government, as upon a boundless ocean, and at a time when the people were accustomed to regard the distinctions of opulence and family as of high importance. But his talents were too great, and his ambition, now roused, was too ardent to be depressed by common opposition. In Rome he assumed the character of an advocate, and his pleadings soon obtained for him both friends and admirers. The interest of Valerila greatly aided his rise to preferment. He was first made military tribune and afterwards quaestor; and, in each of these employments, be attained considenable reputation. He was afterwards joined with Valerius himself in the highest dignities; being the colleague of this nobleman both as consul and censor. Whilst he was quaestor, Cato served in the Roman army under Scipio, in Sicily. He was a great admirer of Fabius Maximus; but not so much on account of his reputation or his power, as for the correctness of his life and manners. The liberality of Scipio's disposition did not accord with Cato's rigid notions of economy. Cato remonstrated with him, in the strongest terms, respecting what he considered a wanton profusion of the public money; but Scipio replied, that his country expected an account of services performed, not of money expended. Unable to check his extravagance, Cato afterwards laid before the Roman senate, a formal complaint against Scipio. The consequence of this was the appointment of commissioners to Sicily, for the purpose of examining into the state of his proceedings. Scipio exhibited, to these commissoners, the state of his troops and his fleet, and dismissed them, highly gratified by his attentions and treatment. On their return to Rome, they informed the senate, that, although the general passed his hours of leisure in a cheerful manner with his friends, yet, that his liberal style of living had not caused him to neglect his duties as a commander. From this period Cato continued to reside chiefly in Rome; where, by his eloquence, he obtained the appellation of the Roman Demosthenes. His excellence, as a public speaker, excited a general emulation among the young men of the city; but few of them were willing to imitate the practice, which he Still continued, of tilling the ground with his own hands, and living in the most frugal and abstemious manner. Few, like Cato, could be satisfied with a plain habit and a poor cottage; or could think it more honourable not to want the superfluities of life than to possess them. Justly, therefore, was be entitled to admiration; for, whilst other citizens were alarmed at labour, and enervated by pleasure, he alone remained unconquered by either. It is said that the garments of Cato were always of the plainest kind; and that, even when he was consul, he drank the same common wine as his slaves. Finery of every description he held in contempt. The walls of his country-house were entirely naked, unadorned either with plaster or whitewash. Through his whole establishment, he invariably preferred utility to ornament. The Romans were chiefly served by slaves; and although the handsomest slaves were those principally esteemed, Cato chose his only by their strength and ability to labour; and, when they grew old, he always sold them, that he might not have anything useless to support. On this subject, however, Plutarch justly says: It is almost impossible to attribute Cato's using his servants like so many beasts of burden, and turning them off or selling them when grown old, to any other than a mean and ungenerous spirit, which accounts the sole tie, between man and man, to be interest or necessity. A good man will take care of those beings who are dependent on him, not only whilst they are young, but when they are old and past service. We ought not to treat living creatures like our clothes or furniture, which, when worn out with use, we throw away. For my own part, (continues this amiable and excellent writer,) I would not sell even an ox that had laboured for me; much less would I banish, for the sake of a little money, a man grown old in my service, for he could be of no more use to the buyer than he was to the seller. But Cato was, in every particular, a rigid mist. He thought nothing cheap that was superfluous; and what a man had no need of, he considered to be dear, even at the lowest price. He used to say, on the subject of pleasure-grounds, that it was better to have fields, where the plough can work or cattle feed, than fine gardens and walks, which require much watering and sweeping." He was a man of astonishing temperance. When a general in the Roman army, his expenditure much less than that of any officer of equal rank. And, afterwards, when he was governor of Sardinia, where many of his predecessors had lavished enormous sums, Cato was of no expence to the public. Instead of using a carriage, as all preceding governors had done, he walked from town to town, attended by a single officer. Indeed, in all things of this description, he was one of the most contented of men; and, in every particular relative to the government and especially in the rigid execution of his orders, none could exceed him. About this period the attention of the public was called to the discussion of a law which had been established about twenty years before, and which required that no woman should possess more than half an ounce of gold, not wear a garment of various colours, nor use a carriage drawn by horses; in any city or town, nor in any place nearer than one mile to a city or town, except when authorized to do so, by joining in some public religious scilemnity. Two of the tribunes now proposed that this law should be repealed; and, at the time fixed for the subject to be discussed, the capitol was filled by an immense crowd of people, some to support and others to oppose it. Nor could even the matrons (says Livy) be detained in their houses, by advice or by shame, or even by the commands of their husbands. They beset every street in the city, and every pass to the capitol. They came even from distant towns and villages, and were urgent with the the consuls, the praetor's, and other magistrates, to grant them a freedom, in these particulars, equal to that enjoyed by the men. They applied to Cato, as one of the consuls, but to no purpose; for he addressed a powerful harangue, against the repeal of what he considered so beneficial a law. They, however, had so much influence as to overpower all his arguments to obtain its repeal; and thus to be allowed wear whatever clothes, and to travel in whatever manner, they pleased. In the year of the city 557, Cato was appointed consul. A consular army was necessary for a war which was carrying on in Spain, and the command of it fell, by lot, to him. The troops, however, with which he had to sail for that country, it cost him much labour to train, so as to be fit for service; and, in the Spaniards, he had to oppose a people, who; both from the Romans and the Carthaginians, had, of late, been gradually acquiring the art of war. On landing in Spain, he immediately sent away all his ships, that the troops which he had brought might place their only hopes of safety in their own valour; and, with asimilar design, when he approached the enemy, he made a circuit, and posted his men on a plain so situated, that the Spaniards were between him and his camp. As they could not, in the former instance, retreat to their ships, so, in this, they could not attain security in their camp but by victory. While Cato was here actively employed, in subdoing some of the people by arms and winning others by kindness, a large army of Spaniards suddenly attacked him, and he was in danger of being totally defeated. In this dilemma, he sent to desire assistance from an adjacent province, and it was promised on condition of his paying a certain sum of money. All the officers of his army were enraged at the idea of the Romans purchasing assistance from people whom they denominated barbarians. But Cato mildly replied: It is no such hardship as you imagine: if we conquer, we shall pay them at the expence of the enemy, and if we are conquered, there will be nobody either to pay or to make the demand. He gained the battle, and never afterwards failed of success. During this expedition, Cato is said to have taken more towns than he had resided days in the country; and much plunder was shared among his soldiers: but he took nothing for himself, except what he ate and drank. When the war was nearly terminated, Scipio, desirous of reaping honour by finishing it, and of thus, as it were, tearing the laurels from Cato's brow, obtained his recal, and the appointment of of himself to the chief command in Spain. But the senate was so satisfied with the operations of their former commander, that Scipio was not suffered to alter anything which Cato had established. The command, therefore, which Scipio had so anxiously solicited, tended rather to diminish his own glory than that of Cato; and Cato, on his return to Rome, was honoured with a public triumph. Some time after this, he accompanied the consul Tiberius Sempronius into Thrace; and he subsequently went, as a legionary tribune, into Greece. The Romans had commenced a war against Antiochus, king of Syria, who, next to Annibal, was the most formidable opponent they had ever encountered. Antiochus had advanced, with his troops, and blocked up the narrow pass of Thermopylae, between the mountains of Thessaly and Phocis. As it was considered impossible to force the pass, Cato, with a division of his troops, under the conduct of a guide, attempted, by a circuitous path, to march into the rear of the enemy. When they had advanced to some distance, it was found that the guide had lost his way, and that they were in the midst of almost impassable rocks and precipices. Conducted by a Roman officer, who was dexterous in climbing steep mountains, Cato moved his troops forward, though at the imminent hazard of their lives; for, in the midst of darkness, they were compelled to scramble along, through wild olive-trees, and among steep rocks. After having long wandered about, apparently to little purpose, the day began to dawn; and, the sound of voices being heard, the advanced guard of the Grecian camp was observed at the foot of the rock. Cato immediately ordered his troops to descend, and surprise the guard. This was done, and one of the men was brought to him. From information given by this prisoner, he was enabled to direct an attack in such a manner that, in a short time, the pass was forced, and the enemy was totally defeated. Though Cato was, at this period, only a tribune, acting under Tiberius, the latter attributed all the merit of the victory to him, and sent him with an account of it, to Rome; that he might be the first to announce the intelligence of his own achievements. So much were the Romans rejoiced at this victory, and so much did it elevate them in their own estimation, that they now believed there could be no bounds to their power. These were the most remarkable of Cato's military exploits. From this time, his attention seems to have been almost wholly applied to civil affairs. As an opponent of Scipio, he supported a charge against, that general, but was not successful; and subsequently, a charge against his brother, Lucius Scipio, who was condemned. Cato himself is said to have been impeached no fewer than fifty times; but he was always enabled to establish his integrity. About ten years after the termination of his consulship, he was a candidate for the office of censor, and had six competitors, all principal members of the senate. Each of the candidates, except himself and Valerius Flaccus, imagining that the people were desirous of being governed with lenity, flattered them with hopes of a mild censorship, expecting thereby to attain the popular favour. Cato, on the contrary, professed his resolution to punish every instance of vice; and, loudly declaring that the city required thorough reformation, conjured the people, if they were wise, to choose not the mildest but the severest physician. He told them that, if he were elected, he would be to them such a physician : he would endeavour to render important service to the commonwealth, by suppressing the luxury of the times. Cato and his friend Valerius Flaccus were the successful candidates; and, soon after the election, they began to perform the duties of their office, by expelling from the senate many persons who had been guilty of misconduct. Among his other proceedings, Cato caused an estimate to be made of all apparel, carriages, female ornaments, furniture, and utensils; and wherever the property of these, in any family, exceeded a fixed sum, it was rated at ten times as much, and paid a tax according to that valuation. This procedure occasioned him numerous enemies, not only among such persons, as, rather than part with their luxuries, chose to pay the tax; but even among such as were compelled to lessen their expences in order to avoid it. With the generality of mankind a prohibition to exhibit their wealth has nearly the same effect as the taking of it away; for opulence is invariably seen in the superfluities, not in tho necessaries of life. Hence, the complaints against the conduct of Cato were innumerable. He had to contend with nearly all the greatest and most powerful men in Rome. Their complaints were incessant; but he paid no regard to them. Many of the most opulent Romans had conducted water from the public reservoirs and fountains, into their houses and gardens. He caused all the pipes by which this was done, to be cut off: he also demolished every building which projected improperly into the streets. He diminished the expence of the public works, and farmed out the revenue, at the highest rent it would bear. These were great public benefits, but they gave excessive offence to many powerful individuals, who endeavoured, by every possible means, to render him odious. The people, however, highly pleased with his conduct, erected to him, in the temple of Health, a statue, on the pedestal of which was the following inscription: In honour of Cato the censor, who, when the Roman commonwealth was declining to decay, set it upright by salutary discipline, and wise ordinances and institutions. No man had ridiculed honours of this description more than Cato; and, in the present instance, when his friends expressed surprise that he had not earlier attained so valuable a mark of public esteem, he replied: I had much rather you should be surprised at the people's having delayed to erect a statue to Cato, than hear you ask why they had erected it. Towards the latter part if his life, the character of Cato seems, in many particulars, to have changed. He now became avaricious; and, as his thirst for wealth increased, he turned his thoughts to various modes of obtaining money. He purchased ponds, hot baths, and property of any kind which would yield him profit. He even practised the most blameable kinds of usury, in lending money at an enormous rate of interest for the use of it. He like wise lent money to his slaves, for the purchase of boys, whom they instructed and fitted for service. These boys were afterwards sold by auction; and Cato deducted, out of the purchase-money, the sums that had been lent, and the interest for the use of them. This was extraordinary conduct for the man who, in Sardinia, had himself been peculiarly severe in checking usury, as a practice extremely injurious to society. Another circumstance observable respecting the old age of Cato is, that although, in his youth, he had been remarkable for temperance, and had considered this one of the most estimable of virtues, he now became fond of conviviality. In the company of his friends, he is said not only to have drunk freely, but sometimes to have sate up all night drinking. Plutarch, however, intimates that the time was passed in rational conversation, and altogether in drinking. Cato (he says) always invited some of his acquaintance to sup with him: and, in the company of these, he passed the time in cheerful conversation, making himself agreeable not only to persons of his own age, but to the young; for he had a thorough knowledge of the world, and had collected a great variety of facts and anecdotes which were highly entertaining. He considered the table as one of the best means of forming friendships; and, at his table, the conversation generally turned upon the praises of great and excellent men among the Romans: of the proffigate and unworthy no mention was made; for he would not suffer, in his company, one word, either good or bad, to be spoken of them. In the day time, Cato chiefly amused himself in writing books, and cultivating the ground. He even wrote a book on country affairs. This, which is his only work now extant, treats, among other things, of the modes of fattening geese, poultry, and pigeons; and of making cakes and preserving fruits. Speaking of himself, when in his seventieth year, he says: I have neither building, nor plate, not rich clothes of any sort. I have no expensive servants, either male or female. If there be anything for which I have occasion, I use it; if not, I go without it. He adds, people censure me because I am without so many things, and I complain of them, because they cannot do without them. The public services of Cato were not yet at an end. A war having broken out between the Carthaginians and Massinissa, king Numidia, an ancient ally of the Romans, Cato, notwithstanding his great age, was dispatched into Africa, to investigate the cause of it. He arrived at Carthage, and, from the extensive preparations which the Carthaginians had made, he imagined that their war with the Numidians was only a prelude to future combats with the Romans. He returned in haste to Rome; and, in a long and emphatic speech, he stated to the senate all the information he had obtained. At the conclusion, he exhibited, in one of the lappets of his gown, some large figs: The country (said he,) where these grew, in but three days sail from Rome. By this action he conveyed to the Romans an idea that the country of Carthage was rich and fertile; and, in his opinion, ought to be conquered and colonized by them. And, afterwards, whatever might be the subject on which he spoke in the senate, he always his harangue with this expression, Delenga est Carthago "Carthage ought to be destroyed". His perseverance was so unremitted, that he, at length, brought about the third and last Carthagian war, in which, though after his death, his desires were effected. Cato survived his son by his first wife; but, by his second wife, the daughter of his secretary, and a very young woman, he left a son, who from his maternal grand-father was surnamed Salonius. This Cato Salonius was the grand-father of Cato of Utica, one of the most illustrious men of his time. Cato himself died, at the age of eighty-five or ninety years; in the year of Rome 605, and 149 years before the birth ofJesus Christ. He was remarkable for four important virtues: industry, bravery, frugality, and patriotism. By his industry, be elevated himself to the highest preferment, nor did he remit it even when he had attained the objects of his pursuit. To the disposal of his time he was always attentive, for he was fully sensible of its value. His bravery is indisputable. His frugality proved by his simple and temperate mode of life. Frugal and its consequences were strength, health, and long life. Frugal of his own fortune, his patriotism led him to be equally so of the public treasure, when committed to his care; and he was, at all times, zealous in reviving and supporting the ancient virtues of his country. But with these various excellences, Cato had great defects and many unamiable qualities. His ambition, being poisoned by envy, disturbed both his own peace and that of the city. As a master, be became stern and unfeeling. His economy degenerated into avarice; and, though he was uncorrupt the management of the public money, he descended to very mean and unwarrantable practices to amass a private fortune. Cato was incessant in censuring the vanity of others, yet he was, himself, excessively vain. Among the instances which have been recorded of this, we may mention his speech after the battle of Thermopylae: Those (said he) who saw Cato charging the enemy, routing, and pursuing them, declared that Cato owed less to the people of Rome, than the people of Rome did to Cato; and, as he came in, panting with exertion, the consul took him in his arms, and embracing him, exclaimed, in a transport of joy, that, neither he, nor the whole Roman people, could sufficiently reward Cato's merit. He used to say, of persons who were guilty of misdemeanors, and were reproved for them by him, that they perhaps considered themselves excusable, as they were not Catos; and, Such as imitated his actions, and did it awkwardly, he called left-handed Catos. He is known to have asserted that the senate, in dangerous times, were accustomed to cast their eyes in him, as passengers in a ship, during a storm, do upon the pilot. His vanity, however, may so far be considered excusable, as his assertions, in all these particulars, were founded in truth; for his life, his eloquence, and his strict integrity, gave him great authority in Rome. In his private character he was an affectionate husband and a good father. He was often known to say that he preferred the character of a good husband to that of a great senator. When we consider how much he was engaged in the management of public affairs, we shall be surprised at the extraordinary attentions which he paid to his son. During the infancy of this son, no private business, however urgent, could prevent him from being at all times present when his wife washed and swaddled him. As soon as the child was capable of receiving knowledge, Cato not only had him instructed by an able grammarian, but also took upon himself much of the office of instructor. Besides training him to literary pursuits, he taught him to throw the dart, to fight hand to hand, to ride, to box, to endure heat and cold, and to swim in the roughest and most rapid parts of the river. This may seem an extraordinary course of instruction; but, as nearly all Roman youths were trained to war, exercises like these, tended, in a peculiar manner, to fit them for a military life. He likewise wrote little histories for his son; by which the boy was enabled to attain a knowledge of the illustrious actions of the ancient Romans, and of the most important customs of his country. He was peculiarly careful that his child should never either witness indecorous actions or hear indecent conversation. There was great singularity in Cato's management of his family. With regard, for instance, to his slaves; none of them were ever suffered to go into the houses of other persons, unless they were sent thither either by him or by his wife. And, if any person asked them what their master was doing, they had express injunctions to answer that they did not know. It was also a rule with him always to have his slaves (if possible) either employed in the house, or asleep; because he thought they must then be out of mischief. And he liked those best who slept the most soundly. One of his greatest failings was the unkind treatment of his slaves. When he was young, and had only a slender income, he never found fault with what was served up to his table; but, afterwards, when he had risen to eminence in the state, and made entertainments for his friends, he never failed, as soon as the dinner was over, to correct, with leather thongs, such of his slaves as had been guilty of negligence. He also contrived to excite perpetual quarrels and jealousies among his servants; being fearful that bad consequences might result to him from their unanimity. And, when any of his slaves were accused of a capital crime, they underwent the form of a trial, in the presence of their fellow-servants; and, if found guilty, were put to death. That Cato had some singular weaknesses of character, will appear from the facts which have been already stated; and will be rendered still more evident by noticing his quackery in medicine. He wrote a tract on the mode of curing diseases: and he mentions in it the diet which he prescribed to his family when any of them were sick. He allowed them to eat vegetables, duck, pigeon, or hare. Food like; this, he says, is light and suitable for sick persons; and has no other inconvenience than that of producing dreams. He has even mentioned a kind of charm to be used in the cure of dislocations. But, by his perseverance in his own modes of curing diseases, he is stated to have lost both his wife and his son; That he lasted so long himself was, no doubt, owing, not to his medical knowledge, but to his temperate habits, and his naturally good constitution. Remarhable sayings of Cato The manner in which Cato spoke, was often very remarkable. Plutarch describes it to have been elegant, facetious, and familiar; and, at the same time, grave, sententious, and vehement. Many of his sayings have been recorded. Complaining of the luxurious mode of living among the Romans, he said: It is indeed a hard matter to save, from ruin, that city, where a fish is sold for more than an ox. To so unwarrantable an excess was luxury of the table carried, that salt-fish, from the Black Sea, are said to have been sold for as much as twelve guineas each; and instances of greater extravagance than this occurred during the times of the Roman emperors. On the subject of extravagance, particularly in the table, Cato, pointing to a young man, who had sold a paternal estate by the sea-side, said: What the sea could not have swallowed without difficulty, that man has swallowed with all imaginable ease. Cato once observed, of the Roman people, that they were like sheep. Singly, (he said,) these animals can scarcely be induced to move, but they all in a body follow their leaders. Just such, (he continued) are you Romans. The very men whose counsel, as individuals, you would despise, lead you with ease in a crowd. Exhorting the people to virtue, he observed : If it be by virtue and temperance, that you are become great, change not for the worse; but if by vice and intemperance, change for the better; for you are already great enough by such means as these. He used to say that his enemies hated him, because be neglected his own concerns, and rose before break of day to watch over those of the public: but he would rather have his good actions go unrewarded than his bad ones unpunished; and he pardoned every one's faults with greater ease than his own. He reproved the people for often choosing the same consuls: Ye either (said he) think the consulship of little value, or have but a small number of men worthy of the office. The Romans, on a particular occasion, having sent three ambassadors to the king of Bithynia, of whom one had the gout, another had his skull trepanned, and the third was nearly an ideot; Cato smiled, and observed that they had sent an embassy, which had neither feet,head, nor heart. When he was employed in Greece, he thus joked with his wife respecting the influence which her son had over her: The Athenians govern the Greeks: I govern the Athenians: you, wife, govern me; and your son governs you. Let him, then, use with moderation that power which, child as he is, sets him above the Greeks. Wise men (said Cato) learn more from fools than fools do from wise men: for the wise avoid the errors of fools, but fools do not profit from the example of the wise. Being once rudely treated by a man who had led a dissolute and infamous life, he said, It is upon very unequal terms that I contend with you : you are accustomed to hear reproach, and can utter it with pleasure, but with me it is both unusual to hear, and disagreeable to utter reproach. It was a saying of Cato, that, he liked a young man who blushed better than one who turned pale; and that he did not approve of a soldier who moved his hands in marching and his feet in fighting, and who snored louder in bed than he shouted in battle. Cato was known to assert that, during his whole life, he had never repented but of three things: the first, that he had trusted a woman with a secret; the second, that he had gone by sea, when he might have gone by land; and the third, that he had passed one day without having a will by him. When drawing near the close of life he declared, to his friends, that the greatest comfort he possessed in his old age, was the recollection of the many benefits and friendly offices he had done to other persons. Authorities-Livy, and Plutarch. |